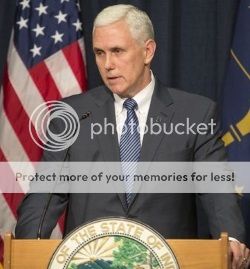

Indiana Governor Mike Pence trying to put lipstick on a pig

In a previous post, I used the title ‘Indiana Ends Fair And Equal Treatment‘ in response to Governor Pence signing a Religious Freedom Restoration Act into law. RFRA’s have opened the door to discrimination since the federal version was used in the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Supreme Court decision back in June.

After my post went up I had a person on twitter try to claim that since the United States Supreme Court had ruled the federal RFRA constitutional and Indiana’s version is an exact copy of the federal version then there is no end to fair and equal treatment. That claim isn’t supported by the facts.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993) was ruled unconstitutional as applied to the states in 1997. Since then 19 states have passed their own versions of RFRAs that apply to state regulations and laws. Many RFRAs are like Indiana’s in that they mandate strict scrutiny be used when determining whether regulations and laws violate the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. That means that a regulation or law must have a compelling governmental interest, be narrowly tailored to achieve that interest, and be the least restrictive means for achieving that interest when it creates a burden on religious beliefs.

If a state passes a rule or law that creates a burden on religious beliefs and it doesn’t conform to the strict scrutiny doctrine called for in the RFRA, then that rule or law wouldn’t apply to people or groups with religious beliefs that conflict with that particular rule or law.

This is where Burwell v. Hobby Lobby and RFRAs open the door to discrimination.

The US Supreme Court decided the Hobby Lobby case based on the federal RFRA and included corporations as people for the purposes of the RFRA. Now corporations, with sincere religious beliefs could use the RFRA to invalidate a rule or law that conflicts with those religious beliefs. Indiana’s RFRA differs from the federal law by explicitly saying corporations are ‘people’ in the text of the law.

Sec. 7. As used in this chapter, “person” includes the following: (1) An individual. (2) An organization, a religious society, a church, a body of communicants, or a group organized and operated primarily for religious purposes. (3) A partnership, a limited liability company, a corporation, a company, a firm, a society, a joint-stock company, an unincorporated association, or another entity that: (A) may sue and be sued; and (B) exercises practices that are compelled or limited by a system of religious belief held by: (i) an individual; or (ii) the individuals; who have control and substantial ownership of the entity, regardless of whether the entity is organized and operated for profit or nonprofit purposes.

There are federal and state laws that prohibit discrimination by businesses or buildings that are open to (or offer services to) the general public. This is called “public accommodation”. A business could use an RFRA to avoid having to comply with public accommodation laws or avoid the legal or financial consequences of not complying with public accommodation laws.

There are numerous state or federal laws that prohibit business from discriminating against employees (and potential employees) or their customers on various grounds, including race, sex, religion, disability, familial status, and, more recently, sexual orientation. Some business owners object to those laws on religious grounds. If the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) requires giving Hobby Lobby a religious exemption from the contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act, does it also provide other businesses with a defense against civil rights laws prohibiting discrimination?

After referring generally to Justice Ginsburg’s concerns, Justice Alito’s decision addresses only one example – race discrimination in employment – which is arguably the least likely to arise in the modern day (Justice Ginsburg’s example was from a 1966 case) and the easiest to resolve. The majority explains that the government may deny an accommodation when the law serves a compelling government interest and the non-discrimination rule is narrowly tailored to that interest. In the context of racial discrimination in employment, the Court writes, the government “has a compelling interest in providing equal employment opportunity to participate in the workforce without regard to race, and prohibitions on racial discrimination are precisely tailored to achieve that critical goal.”

One might be forgiven for assuming that the same is true of the other forms of discrimination mentioned by the dissent. But that assumption is surely open to debate. That is because the Court has, in other contexts, distinguished between racial discrimination, on the one hand, and sex and disability discrimination, on the other. For example, under the Equal Protection Clause, the Court applies strict scrutiny – the same test it applied in Hobby Lobby today – to laws that discriminate on the basis of race, but only “intermediate” scrutiny to sex discrimination, and only “rational basis” scrutiny to disability discrimination (and, up to this point, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation).

Does that mean that the government may only have the “compelling” interest required by RFRA in proscribing racial discrimination, but not sex, disability, or sexual orientation discrimination? As far as I know, the Court has never decided that question in the RFRA context or any other.

Analysis: Hobby Lobby and claims for religious exemptions from anti-discrimination laws?

Supporters of the law in Indiana were not shy about wanting to add religious exemptions for corporations similar to the Hobby Lobby decision:

[Mike Fichter, president and CEO of Indiana Right to Life] said the organization backs the new law because of a desire “to provide greater protections for pro-life businesses and ministries in Indiana.” He cited the case of Hobby Lobby, which was sued after it objected on religious grounds to an Affordable Care Act requirement that the company cover certain contraceptives for women.

The business eventually won a fight in federal court, but Fichter said the federal RFRA act would not protect companies such as Hobby Lobby from state laws. That’s why, he said, the new law is needed in Indiana.

Georgia was considering a similar RFRA until an amendment was added that would not allow the law to be used to avoid state and local nondiscrimination laws. The supporters of that RFRA didn’t try to lie that the law wasn’t to discriminate like the Governor in Indiana has been claiming about his new law.

As it stands now, in Indiana, a cake maker or florist could refuse to serve LGBTQ people and invoke the RFRA to escape any legal or financial issues for violating a law or rule.

That is why my original post was correct in being titled ‘Indiana Ends Fair And Equal Treatment’.

And don’t get me started on the fact that RFRAs give extra special privileges to the religious that are not given to atheists or other secular people.

RFRAs are bad laws all around.

*Update 3/30/15*

The Indiana RFRA also allows religious freedom to be claimed in disputes between private individuals:

Every other Religious Freedom Restoration Act applies to disputes between a person or entity and a government. Indiana’s is the only law that explicitly applies to disputes between private citizens.* This means it could be used as a cudgel by corporations to justify discrimination against individuals that might otherwise be protected under law. Indiana trial lawyer Matt Anderson, discussing this difference, writes that the Indiana law is “more broadly written than its federal and state predecessors” and opens up “the path of least resistance among its species to have a court adjudicate it in a manner that could ultimately be used to discriminate…”

The Big Lie The Media Tells About Indiana’s New ‘Religious Freedom’ Law

The group GLAAD “makes note of three leading anti-LGBT activists, Micah Clark, Curt Smith, and Eric Miller, and the extreme anti-LGBT comments they have made” in the group photo of Gov. Pence’s discrimination signing party.